Image Credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

On Thursday, 4 December, NASA will send its first Orion space capsule thousands of miles above Earth before it descends into the Pacific. The mission will pave the way for manned missions deep into space.

On Thursday the new space capsule will launch into space from Cape Canaveral in Florida aboard a United Launch Alliance Delta 4 heavy rocket.

The Orion spacecraft, which was built by Lockheed Martin, could potentially bring humans deeper into space.

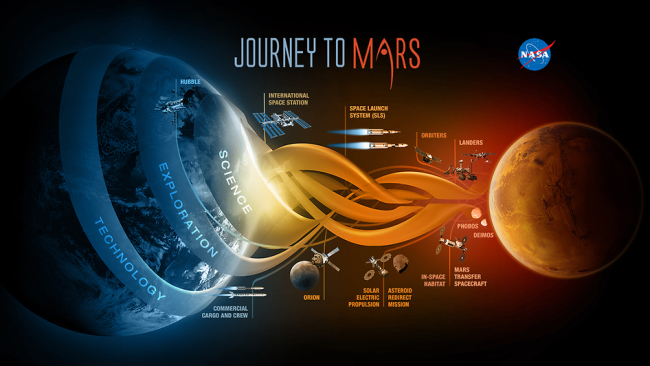

It is envisaged that this means astronauts could be zooming from Earth to Mars by the 2030s.

Thursday’s Flight, called Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1), will travel 3,600 miles (5,800 kilometres) from Earth before rocketing back and descending into the Pacific Ocean, where it will hopefully be retrieved by NASA.

The purpose of the mission is to test the capsule’s heat shield, avionics and other systems.

This is the first time since 1972 when Apollo’s moon missions returned to Earth that attempts have been made to make manned spaceflights beyond the Earth’s orbit.

If the test flight works Orion will be used to land astronauts on near-Earth asteroids and eventually reach Mars.

Poised for lift-off

Orion is poised for a mere 4 1/2-hour, two-orbit mission without anyone on board, the cone-shaped craft needs to perform its roster of tasks well, including an all-important descent through Earth’s atmosphere and splashdown.

“Really, we’re going to test the riskiest parts of the mission,” Geyer said. “Ascent, entry and things like fairing separations, Launch Abort System jettison, the parachutes plus the navigation and guidance – all those things are going to be tested. Plus we’ll fly into deep space and test the radiation effects on those systems.”

The flight test begins at Space Launch Complex 37 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. A 2-hour, 39-minute launch window opens at 7:05 a.m. EST so the launch and recovery of the spacecraft after splashdown can both take place in daylight. Orion will lift off on the strength of a United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy, currently the largest rocket in America’s inventory. The three RS-68 engines will produce about two million pounds of thrust at liftoff, enough to push the 1.63 million pounds of spacecraft, rocket and cryogenic fuel straight up off the launch pad and into orbit.

The boosters on either side of the rocket will fall away about four minutes into the ascent. The center booster with the second stage and Orion on top continues on for about 90 seconds more before its fuel is burned up and it separates to fall back to Earth. From there the second stage will lift Orion while the structural support fairings around the simulated service module fall away, followed closely by the launch abort system.

At 17 minutes, 39 seconds following liftoff, the Orion and second stage will be in an initial orbit of 115 miles by 552 miles. The second stage will ignite again two hours into the flight to send Orion through the Van Allen radiation belts and to a peak altitude of 3,609 miles, some 15 times higher than the space station. This is going to be a key point in the test flight as instruments inside Orion record the radiation doses inside the cabin – critical data for mission planners considering the best way to safely send astronauts into deep space in the future. Orion’s cameras will be turned off during its passes through the belts to protect them.

Three hours, 23 minutes into flight, the Orion crew module will fly on its own following separation from its service module and the Delta IV Heavy second stage. The spacecraft will be aimed at Earth’s atmosphere and it will be up to Orion’s onboard computers to set the spacecraft in the right position so its base heat shield can bear the brunt of the intense reentry heat.

Hitting the atmosphere at 20,000 mph four hours and 13 minutes after launch, Orion will encounter about 80 percent of the heat it would endure during a return from lunar orbit with astronauts aboard. Ground controllers will lose contact with Orion for 2 1/2 minutes during reentry when the spacecraft is surrounded by plasma.

They should regain communications with the craft just before the forward bay cover is jettisoned in a process that will begin the parachute deployment.

After about four hours, 23 minutes, Orion will be bobbing in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Baja California as recovery forces move in.