Minister of State for Research and Innovation Sean Sherlock, TD, ISPAI's Paul Durrant, Boards.ie's Tom Murphy and solicitor Simon McGarr debate at Dublin's Science Gallery last week

Ongoing debates about digital media, copyright reform, piracy and internet freedom are just ‘raindrops’ in a much bigger flood that is about to hit the internet.

It is now 2012, more than 13 years after Napster was created and a piracy nightmare for the music industry and Hollywood began.

Illegal file sharing is claimed by Hollywood and the music industry to be responsible for the wholesale destruction of revenues they once enjoyed.

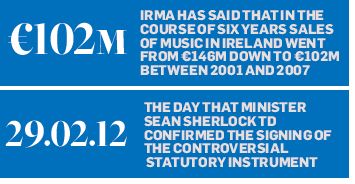

They reckon that one in every 20 downloads online is illegal and locally IRMA claims its members’ revenues fell from €146m in 2001 to €102m by 2007.

In those 13 years, a mechanism or business model that the technology world and content creators can agree on has yet to emerge.

While there are hints in terms of the popularity of services like Spotify, Netflix and iTunes, the truth as I see it is many in the content-creation industries failed to appreciate the significance of the rise of the internet and everything that came with it.

The networks are getting faster, the devices are proliferating, yet media owners are bemoaning losses of revenue and declining market share.

Litigation

In fighting back, many traditional media owners chose the litigious route. At first they sued the individuals one by one and in recent years moved towards getting telecoms companies and ISPs to implement ‘three strikes and your internet gets cut off’ remedies.

And that’s what brought us to where we are today. After Eircom agreed to an out-of-court settlement to implement such a policy, other operators such as UPC decided to fight against it. A court battle ensued and in a case between EMI and UPC, the judge, Mr Justice Peter Charleton, revealed in late 2010 he could not rule against UPC because of a loophole in our copyright laws.

This required the signing of a statutory instrument in February this year that gives judges the power to grant injunctions against ISPs in cases of copyright infringement.

The signing of the statutory instrument amending the Copyright Act 2000 is viewed by many in the internet industry as a retrograde step that could infringe on civil liberties, inhibit innovation and upset internet giants like Google and Facebook that invested in Ireland and could potentially be hit with injunctions.

This could threaten all that Ireland has achieved in becoming the ‘internet capital of Europe’.

Irish Government understanding issues

The general view in the technology industry is that the Government of Ireland failed to understand the technological issues, buckled under legal pressure from the music-recording industry and signed into law a statutory instrument that is as vague as it is dangerous.

However the debate in Ireland, which coincided with the SOPA (Stop Online Piracy Act) controversy in the US, where politicians and law makers scrapped the law to allow for real reflection, is one facet of a global chain of events ranging from the arrival of the AntiCounterfeit Trade Agreement (ACTA) to the enshrining of the internet as a human right by the European Court of Justice.

Minister of State for Research and Innovation Sean Sherlock’s presence at the debate last week in Dublin’s Science Gallery is perhaps unique in this whole battle because few members of government anywhere in the world have provided such a level of access to the public at this stage.

The night before, the event dominated the Twittersphere because of Sherlock’s reluctance to have eloquently outspoken IP law solicitor Simon McGarr at the event. However, on reflection, he changed his mind and said he had no objection to McGarr being on the panel.

“I want to extend the hand of friendship to you, Simon, to move on with this debate,” Sherlock began in his address.

Sherlock spoke of how the statutory instrument is just one facet of an overall strategy leading to the ongoing Copyright Review and he urged people who really care about the debate to take part in the review process.

Paul Durrant, GM of the ISP Association of Ireland (ISPAI) spoke about how dangerously vague the statutory instrument is and how we need to provide greater certainty in Ireland not only to ISPs, but also the multinationals investing the country.

Boards.ie founder Tom Murphy spoke of the dangers of the statutory instrument from the perspective of innovation and freedom of speech and the legal pressure it could exert on publishers and intermediaries.

McGarr said a nation’s copyright laws are a reflection of that country’s approach to innovation.

The unknown follows statutory instrument debate

The frightening part of the entire statutory instrument debate in Ireland is how much we really don’t know lies ahead of us.

That thought ran through my mind when I pointedly asked Durrant had any of his members received letters from labels in the aftermath of the passing of the statutory instrument that many fear will leave ISPs, intermediaries and private citizens open to court battles. He replied they had.

But the enormity of what is ahead – and for which Ireland as a nation does not seem to be adequately prepared, or to be preparing itself – is ownership of the internet, not just the content, but basic freedoms.

Murphy described the statutory instrument as a “raindrop” compared to the flood that will soon envelope us.

The question most people are asking is, who really is open to being sued by record labels if someone shares a video or song on Facebook? Me, you, Facebook, YouTube, the ISP? A second alternative statutory instrument that may have been less harmful and divisive apparently may not have even been seen by the attorney general, a factor that was raised amid a furious debate between Murphy and Sherlock.

For much of the debate, Sherlock was emphatic that signing the statutory instrument was one step on a road that involves the work of the Copyright Review Commission to deliver new copyright legislation that would put Ireland at the forefront of digital legislation and innovation.

He said the key was to devise legislation that meant intermediaries like Boards.ie in the event of a transgression by a member of the public wouldn’t have to put aside a massive war chest of funds to deal with lawsuits, in particularly spurious claims.

McGarr, who along with Michele Neylon and TJ McIntyre tabled the Stop SOPA Ireland petition that attracted 80,000 signatures, returned constantly to the fact that the will of the people of this country wasn’t taken into account and that an important middle ground has been abandoned.

Durrant echoed Murphy’s concerns that the statutory instrument in its current form is too vague and presents more dangers than solutions. He said it deals in particular with third-party content and this is an area that could have grave consequences for emerging sectors, like cloud computing.

“We need certainty in this country where we are trying to retain the multinationals.”

A threat to innovation

Murphy made the point that the statutory instrument threatens innovation investment. “The copyright laws are a reflection of our country’s innovation.”

Some can argue that the very technologies that should allow digitised versions of traditional media – from music and film to newspapers – to flourish are in fact accelerating their demise. The reality as I can see it is that both segments are out of sync. Innovators are innovating with new technologies all the time, content creators and owners are stuck in the halcyon days of sales of physical copies.

ISPs fear laws that could prove to be far too onerous to police while international internet firms want to power ahead without having to handle spurious claims.

At the same time, the simple truth is copyright infringement is theft. Without the ability to earn revenues for the content they have created, thousands of creative and media jobs around the world and not just in Ireland are endangered.

The dream we all share is to make Ireland the home of digital media. It is a nation of storytellers, musicians and artists, it should be a good home for global digital media.

That means uninhibited innovation and opportunities for all. That also means the wheels of business turning so that the research, investment and salaries can all be paid for. It is up to all sides to work together if they really value a future.