This morning it emerged that the UK’s current ICT programme of study in schools is to be scrapped and replaced by a computer science curriculum as the UK quite rightly attempts to revive the legacy laid by Alan Turing in the 1930s that gave rise to computing today.

For the past couple of months, I have been in total awe of the efforts of young Irish programmers like Harry Moran (13), James Whelton (19) and Shane Curran (11), not to mention the huge surge of interest that movements like Coder Dojo have inspired locally in Ireland and lately in the UK.

Everyone I spoke has been unanimous – we need a computer science curriculum in our schools if we are to prepare our young for the jobs of the future.

Like the UK, Ireland has also made its contribution to the foundation of modern computing.

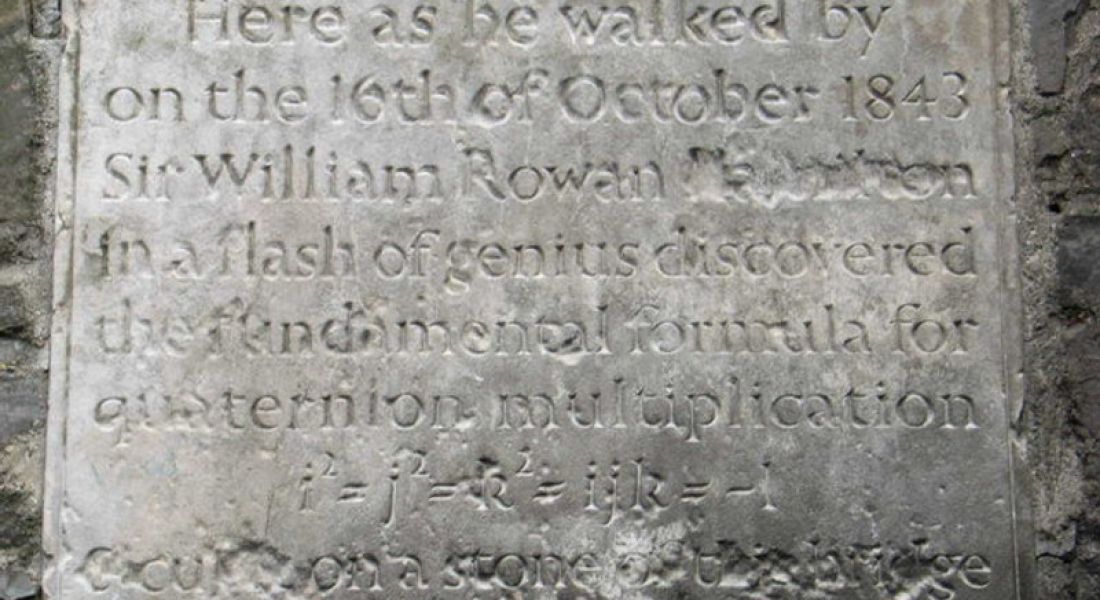

Beyond the obvious concentration of eight out of 10 of the world’s biggest computer manufacturers being in Ireland, in the 19th century Sir William Rowan Hamilton a mathematician, physicist and astronomer at Trinity College Dublin wrote out the formula for quaternions, which are the key to the breathtaking graphics we see in today’s modern video games – if you don’t believe me, the evidence is on Broom Bridge in Dublin. In 1843, Hamilton was out walking with his wife when the equation came to him and with a penknife he committed an act of vandalism that has helped make today’s digital revolution possible.

Policymakers asleep at the wheel?

Unfortunately, this is something that isn’t taught to Irish schoolchildren. If you ask me, Irish education has been technologically averse, and the fear is palpable. The decision makers fear change. Perhaps in the same way education publishers fear digital editions, tablet computers or e-books.

Ireland’s education system’s efforts at putting computers in schools since the beginning of the century have been disastrous. A strategy that began in 2000 resulted in the few teachers that championed it becoming disillusioned, seeing themselves as glorified IT managers servicing out-of-date computers.

An industry-supported initiative to be called Smart Schools = Smart Economy in 2009 had all the right intentions – computer training and laptops for every teacher, digital projectors in every classroom, and a focus on continuous professional development for the teachers.

However, this too became a victim of the economic downturn and despite some successes in various schools, I have heard some principals have used their grant allocation to keep the lights and heat on in their schools.

Equipment strategies will come and go and yes, many kids will have computers in the home, smartphones in their pockets and broadband will eventually trickle its way to each school, but what is really needed – what is truly needed – is computer science on the curriculum.

Coding, for example, will be a language that will be fundamentally more important to the business world than speaking a foreign language was in the 20th century.

In the years ahead, jobs will require the minimum of coding ability, along with the ability to conduct complex analytics and compile spot-on statistics and intelligence. The business world has gone digital and there will be no looking back. Mathematical ability, analytical ability and critical thinking skills, as well as good team working skills will be essential to be employable in the 21st century.

The IT industry in Ireland currently has 5,000 job vacancies it can’t fill and this is at a time of high unemployment.

Our third-level sector needs the best and brightest already in sync with the latest technologies if it is going to serve this need and the only way to do this is to make brave decisions now that will resonate in the decades to come. A computer science curriculum is part of the answer.

It requires bravery and vision beyond the outdated by-rote methods that endure today.

Yesterday, Education Minister Ruairi Quinn launched an EU-funded €3.7m initiative that it is hoped will revolutionise how science is taught in the classroom. It’s a pan-European effort that will be co-ordinated by DCU and will involve 12 European countries.

It’s no doubt a worthy initiative that addresses a worldwide problem, and of course ahead of this week’s BT Young Scientist & Technology Exhibition where thousands of brilliant young minds will demonstrate their ability to drive change, it’s good PR.

But it doesn’t address the underlying ICT problem. If the UK can face up to the fact its ICT programme for schools isn’t working, then a country like Ireland that currently has no ICT programme in schools whatsoever, and yet whose very destiny and existence is tied up with the fate of the IT industry, needs to do something radical.

But putting in place a computer science curriculum isn’t radical – it’s simply pragmatic. It’s overdue. So wake up.