An artist's rendering of a solar roadway

A US engineer is looking to turn roads and car parks into one giant solar energy plant with the help of his small start-up, Solar Roadways.

The man behind the project, Scott Brusaw, has gained some influential followers in science and the US government who have become involved in funding his idea, potentially making it a viable and important technology.

So far, Brusaw has received significant funding from the US Federal Highway Administration to develop his early prototypes for the solar road panels, which are created by using a combination of plexi-glass, solar panels, circuitry and LED lights.

The obvious questions remain, however, such as how does a car gain traction to drive on glass, especially under wet conditions; how does it deal with snow, which could cover the solar panels, and also how the roads would be able to cater for road markings.

Of course, all these issues have been taken on board by Brusaw, who uses a form of plexi-glass that is more akin to driving on steel than window glass, while the circuitry and LED lights contain heating elements that not only heat the road to prevent a build-up of ice and snow, but enable the use of LEDs for standard road markings and messages that pop up on the road itself to warn drivers of accidents ahead.

The roads could also allow for electric-car drivers to pull over and charge their cars at charging points dotted along the roadway and reduce the need for establishing specific charging points in a similar fashion to Tesla’s cross-country endeavours with its own electric car brand.

By Brusaw’s calculations, in the US alone, there are almost 50,000 sq km of asphalt surfaces that could potentially be converted to the Solar Roadways solar panels that could produce 21,827bn Kilowatt-hours of electricity annually.

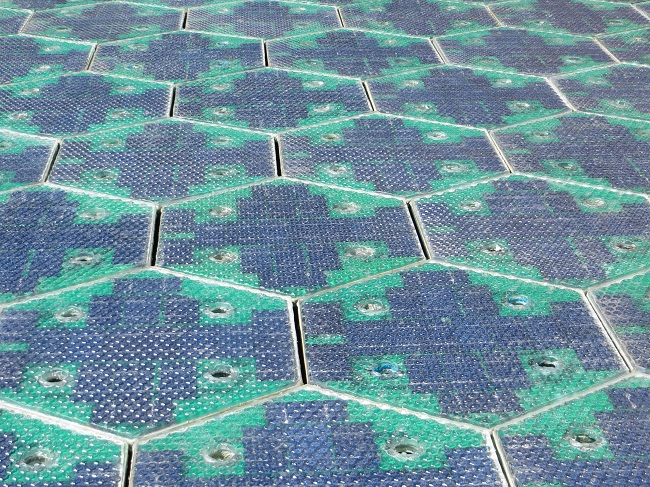

A close-up of the solar panel prototype developed by Solar Roadways

If this technology were indeed to take off, this would cut the greenhouse gas output of the US by 75pc, as many shops and larger stores would be able to feed directly off the electricity generated on the street and car park directly outside.

The obvious question remains of how much would a solar roadway cost manufacturers and governments in installation? Experts largely consider the project as being far from feasible at the current cost of production.

While Brusaw’s point about the rising cost of petroleum having a knock-on effect with the price of asphalt, the cost of solar panels still does not take into account the fact that asphalt roads have a life expectancy of decades, much longer than solar roadways’ seven years, as Brusaw speculates.

Like much clean-technology in the current economy, the fact the cost-effectiveness remains on the more negative side means solar roadways are unlikely to be feasible for at least a decade or more.

Another element to consider is that even if these solar panels were cost efficient and generating the amount of electricity Solar Roadways expects a fully integrated system to produce, there would still remain the problem of digging up this estimated 50,000 sq km of asphalt in the US and replacing it with the solar roads.

These types of challenges are what lies ahead for Brusaw and his Solar Roadways project, but if there is a chance in the foreseeable future of this technology being adapted by some of the world’s largest nations, the way we consume and produce electricity could change forever.