Douglas Engelbart in 2008. Image via Wikimedia Commons

The internet world is in mourning today as Douglas Engelbart, the US inventor best known for his pivotal work on figuring out the challenges of human/computer interaction, and for co-creating the computer mouse invention, has died. He died at his home in Atherton, California, on 2 July at the age of 88.

Engelbart, known as Doug, was born in Portland, Oregon on 30 January 1925.

During his third-level education at Oregon State College near the end of World War II, he was drafted into the United States Navy. Engelbart served two years as a radar technician in the Philippines.

He would return to Oregon State College, where he completed his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering in 1948.

He was hired by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics at the Ames Research Center, where he worked in 1951.

Epiphany

Engelbart appears to have had what people often describe as an ‘epiphany’ in 1951, the year in which he was engaged to be married.

He seems to have decided that he wanted to play a part in making the world a better place by harnessing the collective human intellect to find better solutions to problems. As part of his vision, Engelbart decided that computers would be the way forward for finding such collective solutions.

He enrolled in graduate school in electrical engineering at University of California, Berkeley, where he graduated with a master’s degree in science in 1953 and a PhD in 1955.

While at Berkeley, Engelbart helped in the construction of the California Digital Computer project known as CALDIC. This was an electronic digital computer built with the assistance of the Office of Naval Research at the University of California between 1951 and 1955.

The idea of CALDIC was to assist the research being conducted at the university by providing a platform for high-speed computing.

After he finished his PhD, Engelbart stayed on at Berkeley as an assistant professor to teach for a year.

He then left to set up his own start-up called Digital Techniques. The idea of the start-up was that it would help Engelbart commercialise part of his doctorate research on storage devices.

After a year, however, he pivoted again, and decided to pursue the research he had been envisioning since 1951.

Stanford Research Institute

He took up a position at SRI International (known then as Stanford Research Institute) in Menlo Park, California, in 1957.

First off, he worked for Hewitt Crane.

While at SRI, Engelbart obtained more than a dozen patents over an organic timeframe, some of which were spawned from his graduate studies.

In 1962, Engelbart released a report about his vision and proposed research agenda. The report was entitled Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework.

This sparked funding from ARPA to launch his work.

Engelbart recruited a research team for his new Augmentation Research Center (ARC) at SRI in California.

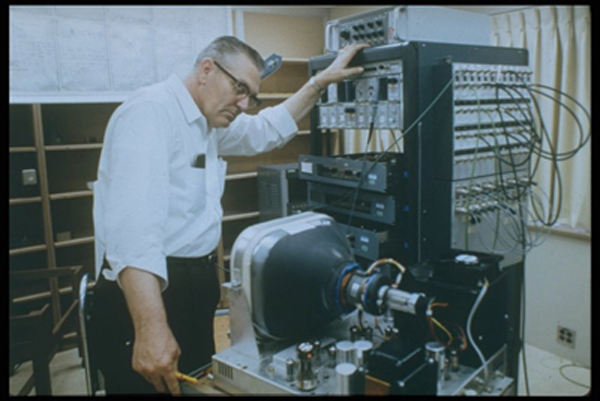

Engelbart pictured at ARC in the 1960s. Credit: SRI International

Pioneering computer interface ideas

Together with his team, he developed pioneering computer interface elements, such as bitmapped screens, the mouse, hypertext, collaborative tools, and precursors to the graphical user interface.

It is believed he came up with many of his user interface ideas back in the mid-1960s – long before the onslaught of the personal computer revolution.

SRI’s first computer mouse prototype. Image via SRI International

The mouse

So what type of patents did he apply for and get? The computer mouse, for instance.

In 1967, he applied for a patent for the wooden shell with two metal wheels, which he had co-developed with Bill English, his lead engineer.

In the patent application it is described as an “X-Y position indicator for a display system”. Engelbart would later divulge that it was nicknamed the ‘mouse’ because the tail came out the end.

The patent was accepted in 1970.

Engelbart never received any royalties for his mouse invention. That’s because SRI appeared to have no real idea of the mouse’s value when it patented the device.

Rumours have since circulated that SRI had licensed the patent for the ‘mouse’ to Apple Computer for about US$40,000.

What happened next …

Engelbart also showcased his corded keyboard and many more of his and ARC’s inventions in 1968.

Engelbart’s research was funded by DAPPA, while SRI’s ARC would become involved with the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET), the precursor of the internet.

The ARPANET was one of the world’s first operational packet switching networks. It was the first network to implement TCP/IP, a set of communication protocols were developed by computer scientists Robert Kahn and Vinton (Vint) Cerf.

As for Engelbart, some of his researchers left his organisation for Xerox PARC around 1968. There appears to have been differing views between Engelbart and certain researchers as to the future of computing.

Engelbart has been described as having a vision for collaborative, networked client-server computers, while some of his programmers were veering towards the personal computer.

In 1969, a collusion of events happened to change the direction of Engelbart’s research. The Mansfield Amendment ended military funding of non-military research, the end of the Vietnam War and the end of the Apollo programme reduced ARC’s funding from ARPA and NASA.

SRI’s management placed the remains of ARC under the control of artificial intelligence researcher Bertram Raphael, who negotiated the transfer of the laboratory to a company called Tymshare

Engelbart’s house in Atherton, California, also burned down during this period.

Tymshare took over NLS and the lab that Engelbart had founded. It hired most of the lab’s staff, including Engelbart as a senior scientist.

It seems that at Tymshare Engelbart became marginalised as a researcher and almost demoted.

In 1984, McDonnell Douglas acquired Tymshare, but is believed to have never committed the funds or the people to develop Engelbart’s ideas.

The pursuit of his creative vision

Engelbart retired from McDonnell Douglas in 1986 as he wanted to liberate himself from the commercial world in order to pursue his own ideas.

Together with his daughter, Christina Engelbart, in 1988 he founded the Bootstrap Institute to bring his ideas into a series of management seminars that were offered at Stanford University between 1989-2000.

The Bootstrap Alliance was formed as a non-profit base to help bring some of Engelbart’s ideas to the commercial arena.

However, the invasion of Iraq and the subsequent recession in the US forced some belt-tightening in terms of funding for Engelbart’s research.

In the mid-1990s, the team was awarded some DARPA funding to develop a modern user interface.

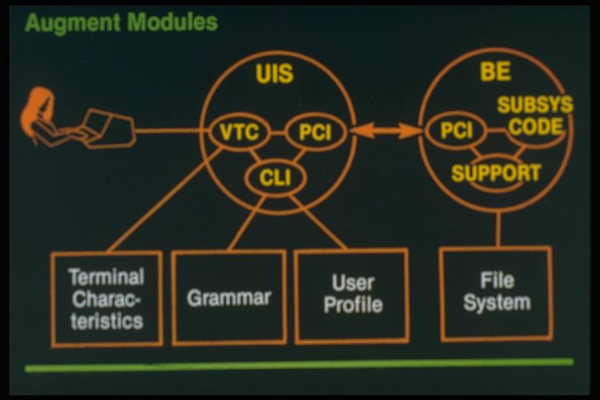

Client server architecture. Image credit: http://www.dougengelbart.org

Global recognition

In 1995, at the fourth WWW Conference in Boston, Engelbart was the first recipient of what would later become known as the Yuri Rubinsky Memorial Award

In 1997, he was awarded the Lemelson-MIT Prize of US$500,000, the world’s largest single prize for invention and innovation, and the ACM Turing Award.

Then, in 1998, to mark the 30th anniversary of Engelbart’s 1968 demo, the Stanford Silicon Valley Archives and the Palo Alto, California, think-tank Institute for the Future hosted a symposium at Stanford University to honour Engelbart and his vision. The event was dubbed Engelbart’s Unfinished Revolution.

In 2000, then-US President Bill Clinton awarded Engelbart the National Medal of Technology, the United States’ highest technology award.

Engelbart took part in the Program for the Future 2010 Conference.

Augmenting collective human intelligence

Hoards of people met at The Tech Museum in San Jose, California, and online to thrash out ideas on how to pursue his vision to augment collective intelligence.

In terms of his personal life, Engelbart had four children, Gerda, Diana, Christina and Norman with his first wife Ballard, who died in 1997 after 47 years of marriage.

He married writer and producer Karen O’Leary Engelbart in 2008.

Engelbart was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2007. He died seemingly peacefully in his sleep.

He is survived by his wife, four children, and nine grandchildren.

Engelbart often concluded his presentations with this inspirational parable of soaring elegantly up above the horizon. Credit: http://www.dougengelbart.org