Marine researcher Dr Margaret Rae

Dr Margaret Rae and colleagues on the Beaufort Marine Biodiscovery Project are looking to the sea in the hunt for clinically useful molecules. She tells Claire O’Connell about the hands-on chemistry of screening the marine for new and interesting chemistry.

When you look at the sea, what do you see? Possibly not too much from the surface, but from a chemist’s perspective the organisms that live in and around the sea – from the coast to the deep – are a potential treasure trove of weird, wonderful and maybe even clinically useful molecules. And Dr Margaret Rae is looking for them.

She and her colleagues in the Beaufort Marine Biodiscovery Project plumb the depths and comb the beaches for marine life in the search for ‘bioactive’ molecules that could be of use for tackling microbes, inflammation, human diseases and maybe even cancer on dry land.

Have chemistry degree, will travel

Rae didn’t start out as a marine researcher, though. Her background is squarely in chemistry, and her initial degree from University College Dublin has been a passport to various types of jobs, including analysing water quality, working on eco-friendly electronics, a PhD in Portugal on the chemistry of fullerenes, troubleshooting software and hardware in the chemical industry and setting up a quality system for adult human stem cell use at the Regenerative Medicine Institute in Galway.

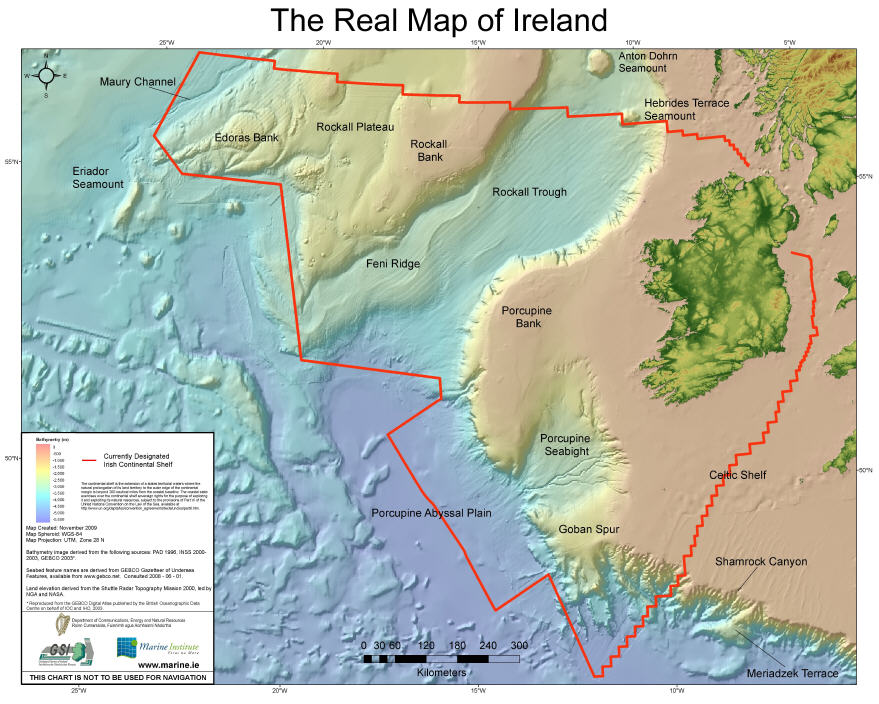

But eventually chemistry research lured her back into the lab, and she became involved in the Marine Institute’s biodiscovery programme, a €7.23m initiative that involves Queen’s University Belfast (QUB), University College Cork and NUI Galway, where Rae is now a research fellow at the Ryan Institute. “Ireland has huge coastline and a seabed area 10 times that of the island itself – the programme seeks to explore the biodiversity within our marine national assets,” she explains.

The goal? To find bioactives, or molecules that have a biological effect in an organism, such as a human, animal or plant. “Normally, what we want is a specific effect,” says Rae. “So we will be looking for something that will kill harmful bacteria or cancer cells, or perhaps that has anti-inflammatory effects and maybe can help to prevent neurodegeneration.”

To the sea

But why go looking in the marine for such chemical usefulness? In part it’s a numbers game, according to Rae. “In terms of evolution and differences and metabolic pathways, there’s a greater diversity in the marine than on the terrestrial part of Earth,” she says. “And because of this diversity, the likelihood of encountering compounds that are unknown on land would be much higher.”

Some types of organisms are well known as particularly rich chests of potentially interesting chemicals. They include sponges, seaweeds, microbes, echinoderms (such as sea stars), cnidarians (sea anemones, corals, hydra) and many more, and Rae and her colleagues collect them from the shore through to the deep – though she admits her sea legs are not that used to expeditions on the open seas. She recently spent three weeks aboard the RV Celtic Explorer, and while she relished the chance to go, three weeks of seasickness was hard to stomach.

“It’s something anybody working in the marine environment has to put up with,” she says. “But overall it’s a great opportunity to get on the Celtic Explorer – when I was training as a chemist I never thought that I would be getting out and doing these things.”

Back on the beach, there are also interesting molecules to be found, and Rae works with taxonomist Dr Svenja Heesch to harvest seaweed specimens. “It really puts you in touch with nature,” says Rae, who is struck by the colours when she’s out on the beach. “For bench scientists like myself in a lab, you get used to that clinical sterile-looking laboratory and then you go out in the field – the first thing that hits me is the colour, the lovely blues and greens and yellows and oranges and browns. It really is something really different.”

She also enjoys the start-to-finish cycle of discovering an active molecule: “I can go out there and get my samples whether on the coast or out at sea, then I can do an entire workup on those specimens from collection through to extraction right up to partitioning, fractioning, trying to find and isolate the bioactives,” she says.

With such an elaborate workup it’s really necessary to keep track of everything and Rae works with another colleague, Dr Helka Folch at QUB, to ensure that all the data generated by all biodiscovery scientists – all the specimens, their locations, habitats, extractions, fractions, and bioassay results are stored and can be queried at any time. “Helka is guardian over the database, a gargantuan task,” says Rae.

Bioactive hits

So far, Rae and her colleagues have identified several interesting bioactives from marine species. “We have found around 10 extracts that would have some form of anti-cancer activity, and we are particularly interested in two or three of those, where we are seeing very specific anti-cancer activity,” she says. “We have also found anti-inflammatory activity and within the [Beaufort] partnership we have found anti-bacterial, anti-fungal and some bacterial quorum sensing for extracts and compounds.”

When they find a bioactive of interest the next step is to isolate more of it and work out the molecular structure with Prof Deniz Tasdemir and her team of scientists at NUI Galway. “If it’s very interesting and not enough can be sustainably harvested, we follow up and see whether or not the compound could be artificially made in the lab,” says Rae.

And while it can be time consuming work to harvest samples, rush them back to the lab to preserve the potential biomolecules and then comb the extracts for biochemical activity, seeing a positive result keeps the interest stoked, she notes. “When you get that initial ‘hit’ of a bioactive in an extract, you get really enthusiastic all over again.”

Women Invent Tomorrow is Silicon Republic’s year-long campaign to champion the role of women in science, technology, engineering and maths