Apple's iPhone 5 running iOS 6

Apple’s iOS 6 update came with new privacy settings that have been applauded by a US rights advocacy group and Ireland’s own Data Protection Commissioner – but one update in particular has caught the attention of data protection experts who question the tech giant’s compliance with EU law.

Users may have noticed a number of websites – particularly those in the UK – now ask for their permission to enable cookies. This is because of the EU e-Privacy Directive, which requires that consent is given to use cookies other than those strictly necessary for the delivery of a service requested by the user (for example, cookies that track what items are stored in an online shopping cart would be deemed necessary).

This directive was brought into Irish law last year under SI 336. The cookies legislation has been heavily focused on web browsers, but it is widely accepted that the scope of the directive covers any ‘cookie-like’ technologies.

Recently, it was discovered that Apple introduced user-tracking technology that operates similarly to cookies with its iOS 6 update. This technology is enabled by default and, though users can switch it off, how to do so is not made clear.

A closer look at the technology

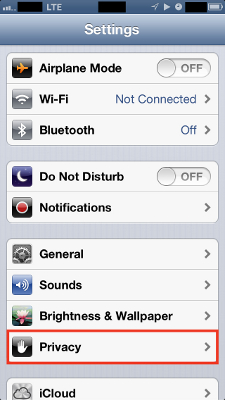

Apple has received praise from the Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT) for the “privacy-enhancing features” it introduced with iOS 6, particularly the introduction of a ‘Privacy’ tab in the settings menu which gives users greater control over the data they share with apps.

However, the settings for ad tracking are not to be found here. To access these settings, users must go to the ‘General’ tab, then ‘About’, then ‘Advertising’. Here they will be able to switch ‘Limit Ad Tracking’ on, which will turn tracking off – a convoluted and counter-intuitive process.

This tracking technology was introduced earlier this year as identifierforAdvertising, or IDFA. (Though the property has been renamed as advertisingIdentifier in the iOS Developer Library, I will continue to refer to it as IDFA throughout this article). Along with two other new identifiers, IDFA is intended to replace unique device identifiers (UDIDs), which Apple has discontinued in response to a number of privacy issues.

The first, identifierforVendor, can be used by app developers to recognise a device across their entire family of apps. The second is a universally unique identifier (UUID) that is specific to a single app. And, finally, IDFA can be used by third-party advertisers to deliver, measure and target advertisements to users.

IDFA works very much in the same way that cookies do on the web, but there is a key difference. With cookies, each ad network receives a unique identifier for every user that only it can read. With IDFA, the identifier is universal, meaning ad networks could potentially share and trade users’ data, tracking their activities across any other network installed in any app.

Why is this legal?

So, any iPhone using iOS 6 contains technology that operates like a cookie, tracking the user and sending this data on to advertisers, and not only is the user not made aware of this technology upon first use of iOS 6, the option to opt out has been buried in the settings menu. You would think this would put Apple on the wrong side of EU law, but it appears not.

While both the CDT and Ireland’s own Office of the Data Protection Commissioner (ODPC) agree that the opt-out setting could have been made clearer and simpler, its very existence has earned praise for Apple.

Daragh O’Brien, a data protection and information governance consultant and trainer who is also managing director of Castlebridge Associates, finds this response at odds with his own research. “It adds further confusion to what the rules of the game are in relation to the use of cookies for tracking in web and other contexts, and highlights how it is confusing even for experts to figure out what is actually required under the e-privacy regulations at this stage,” he said.

“With IDFA, the identifier is universal, meaning ad networks could potentially share and trade users’ data.”

A necessary evil

O’Brien, who previously expressed his concerns about iOS 6 and privacy on his personal blog, believes the objective of EU data protection law is to strike a balance between users’ privacy and the rights of companies and organisations to legitimately use their data. Just like a pop-up notice asks if an app can use your location data, Apple should be asking iOS 6 users if it can use IDFA technology.

But the ODPC sees things differently. Apparently, all three identifiers have been deemed necessary for apps to function, and how this technology is used is the responsibility of the app developers, not Apple.

“iOS, similar to all other app platforms, has provided APIs that applications can run in order for their app to operate as designed, including APIs for identifiers,” said an ODPC spokesperson. “From a data protection perspective it is the individual app that is the data controller for any data collected and therefore primary responsibility for compliance with e-privacy requirements, insofar as they arise, is [with] the app.”

What this means for developers is yet to be determined as the compliance requirements of apps is being analysed by EU data protection authorities and an opinion on this is expected to be published early next year.

“While the [ODPC] has determined that the identifiers are necessary to allow apps to work, I still would be of the view that, given the identifier is labelled ‘Identifier for Advertising’, individuals should be alerted to that advertising use and be given the opportunity to confirm their consent,” said O’Brien, who questions how ‘necessary’ this technology really is. “I’ve turned off the tracking setting and the apps on my phone work fine, so I can’t see how it is necessary for the device to be tracked for advertising.”

O’Brien points out that the iOS Developer Program License agreement clearly states that IDFA is to be used specifically for the purpose of advertising and nothing more. “It’s also important to note that other sections of that licence agreement grant Apple very strict rights and controls over how data on a device can be accessed and used,” he added. “The licence agreement also places clear onus on developers to get consents as required by relevant laws. ‘Opt-out’ by default and ‘opt-in’ on an app-by-app basis would have been a better solution in my view.”

Power to the advertisers

Dr Paul Bernal – who lectures on information technology, intellectual property and media law at the University of East Anglia in the UK – first came across IDFA technology through an online article that was sent to him via Twitter. While the discovery of this tracking technology aroused concern, it did not surprise him.

“Advertisers are constantly pushing for more ways to track us, and to link their various different sources of data. Mobile technology – specifically smartphone technology – gives them many new sources of data,” he said. “The privacy implications are huge: the possibilities of abuse are immense, as the link between the real world and the online world can be made.”

“The privacy implications are huge: the possibilities of abuse are immense.”

The fact that opting out of IDFA is made difficult also comes as no shock to Bernal. “Ideally, of course, it should be ‘opt-in’ rather than ‘opt-out’, but at the moment advertisers (and Apple) are resisting this very strongly, and for clear reasons,” he said. “They know that, where we’re given a choice, we generally choose not to be tracked – which cuts their data stream.”

Off the hook

It seems that confusion over what technology is covered by EU legislation has given Apple, and advertisers, a lot of power over users’ data. “The so-called ‘cookie directive’ (actually the updated e-Privacy Directive) technically covers things that behave like cookies, but it’s a bit of a grey area,” Bernal explained. “What’s more, the [UK] Information Commissioner’s Office has taken a ‘softly softly’ approach to enforcement, and would be highly unlikely to do anything except make a critical comment about it,” he added.

“When an American mobile advertising company is saying that this is great because it’s on by default and people won’t think to turn it off, that’s usually a sign that it’s not a good thing for the privacy of the consumer,” O’Brien added as food for thought.

Bernal is happy with the privacy update that came with iOS 6, but disappointed in Apple’s overall implementation. “If they had included all the privacy settings in the same place, or, best of all, had made the system ‘opt-in’, they could have been real leaders in privacy,” he said. “They had a chance to take a real lead, and they blew it, instead putting themselves right back in the pack.”