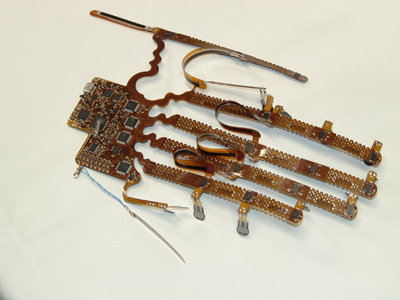

Haptic hand technology being developed at Tyndall National Institute

Tyndall National Institute in Cork is working with clinicians and companies to develop medical devices and technology platforms. We find out more about how expertise at the centre, which is renowned for its work in ICT, materials and photonics, can fit hand-in-glove with clinical needs.

One of the technologies literally does that: called the ‘haptic hand’, the device is a sensorised glove that’s designed to gather information on the dynamics of the wearer’s hand movements. It could have many applications in medicine, including offering an objective way to look at joint mobility in patients with arthritis, explains Dr Paul Galvin, who heads the life science interface group at Tyndall.

“The idea of this technology is that it could potentially be translated readily across the healthcare spectrum to assess the level of arthritis,” he says.

Tyndall researchers are working on the project with Dr Kevin Curran at the University of Ulster and consultant rheumatologist Dr Philip Gardiner at Altnagelvin Hospital in Derry, and the project had its origins through the Science Foundation Ireland-supported National Access Programme, which offers researchers access to the facilities and expertise in Tyndall.

“Our wireless sensors group within Tyndall, headed up by Brendan O’Flynn, was asked to develop a sensorised glove that allows the movement of hand and fingers to be measured,” says Galvin. “This would allow the clinicians to more objectively understand the movements of the hand.”

Sensorised glove technology being developed at Tyndall National Institute

The group at Tyndall National Institute is integrating off-the-shelf sensors into the glove format so information from the sensors can be used to assess joint mobility.

“The sensors will provide a 3D simulation model of the joint movement,” says Galvin. “It will allow a graphic evaluation of the level of hand stiffness and it will let the clinician monitor the movement of the patient over a 24-hour period.”

Now at the prototype stage, the technology could potentially have applications in other areas, too, he adds.

“A similar type of technology could potentially be applied in stroke rehab and training for various movements, including looking at it for the training of surgeons.”

Links with clinicians

More broadly, Tyndall is linking with clinicians to promote the convergence of technologies in med tech, explains Galvin.

“Most of what we do in the medical-device space now is led by clinicians and the medical-device industry,” he says. “We have a long-term strategy looking at convergence and we have identified specific gaps where the clinicians and the engineers can interact and work together on various challenges.”

Tyndall works particularly closely with the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland – they established a memorandum of understanding in 2010 – and with clinicians at Cork hospitals.

Current initiatives include using sensors to track the movements of surgeons to improve training, developing approaches that optimise the surfaces of implantable devices and building technologies to control symptoms by targeting nerves. Tyndall researchers are also working on highly sensitive nanoscale and point-of-care platforms for more convenient and rapid diagnoses.

Company engagement

As well as brainstorming with clinicians, Tyndall National Institute is working with IDA Ireland to engage with companies in the med-tech space, says business development executive Carlo Webster. They include UCLA spin-out Radius Health, which is developing new ‘X-ray on a chip’ technology, Covidien, i360 Medical and Dabl.

Webster describes how, more generally, interest is growing in understanding electronics and microelectronics as part of the move towards smaller diagnostic and therapeutic devices that use silicon and photonics technology.

“There’s a realisation that miniaturisation is going to happen,” says Webster. “And the advantages of putting things on a chip level is that you are starting to remove multiple components and interactions where you have to assemble parts, so you are reducing costs and increasing efficiency.

“There’s a lot of expertise in microelectronics and the semiconductor industry which the med-tech sector is looking to exploit, and at Tyndall we can take a concept from the theory, modelling and design right through to fabrication, packaging and test. This is unique within Ireland and Europe, given Tyndall is a leader in information, communications, technology, photonics, materials and microsystems research,” he adds.

Siliconrepublic.com is hosting Med Tech Focus, an initiative which over coming months will cover news, reports, interviews and videos, documenting Ireland’s leading role in one of the hottest sectors in technology.